"Corkscrew Willow Women" by Colleen Harris

creative nonfiction

Chimpanzees are known to raid stocks of palm wine brewed by villagers, and feral Caribbean vervets snatch boozy drinks from bartops while distracted tourists apply sunblock. Alcoholism and addiction are a natural thing—the Bohemian waxwing gorges itself on fermented winter rowan berries until it cannot fly or walk straight, red-tipped wings carving oblique angles in the air, yellow-edged tail a harmless tracer round following its wavering path. A tiny Malaysian tree shrew has a diet three-point-eight percent alcohol by volume, and bees, like Dekes and white-collar workers, prefer their nectar infused with nicotine and caffeine.

A human child can be trained to know the difference between beer and soda cans, to pour lager into a frozen mug with a perfect half-inch head of foam by the time they are six years old, and to step carefully, so carefully, on the way to waiting calloused hands in an old mauve armchair. This is the first sacrament a daughter remembers, more important than First Communion, and more memorable. Jesus is difficult for a child to conceptualize, after all, and a father in need of his MeisterBrau is something she can touch. By the age of eight, the girl will resent sharing the sacred chalice, and like the black eagle and the Nazca booby, will consider obligate siblicide to preserve her place in the ritual.

Crop circles are blamed on stoned wallabies breaking into guarded poppy fields, eating the flowers, hopping madly in magic marsupial circles. Young dolphins pass pufferfish like community blunts, and after their poison games have been found floating just below the surface, mesmerized by the play of light and air on the water, transfixed by a shifting, liminal beauty invisible to the sober. Animals know: there is something thrilling about intoxication.

***

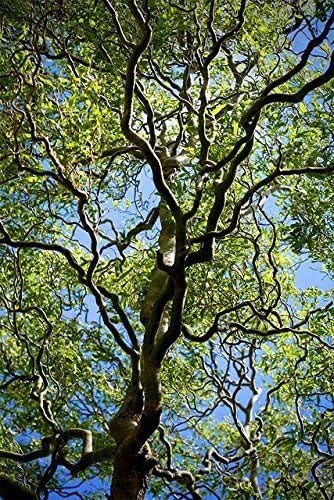

Plants cannot get drunk, though alcohol will stunt leaf and stem growth, and is toxic, causing dehydration, stress, maybe death. Take the curly willow, fast-growing but short-lived. Like a corkscrew willow that in some secret way, despite all its coils and turns, always finds the sun, my mother’s kindness contorts her to believe that I am not, deep down, distorted. But I am her seed, and his, and any gardener will tell you this truth: much depends on the soil.

Much also depends on silence. The things I do not tell her grow roots, a forest thickening in my throat with each passing year until we rarely speak—how, at twelve, I prayed to find her gone each night, a trip for milk turned escape, willing to give her up to a life leagues from a man whose voice was a raised fist. How, at a part-time job in a high-school office, I learned when cops with dogs would come, how, for a few dollars, I let the dealers know. How, for a few more, I sold them orphaned lockers to keep their stashes safe from human sweeps.

I yank myself out by my roots. Kentucky is as far as I get from my New York home, and it is far enough. I discover the smoke of whiskey and the burning curl of bourbon, the throat-singe of Everclear and the spiced fire of Bacardi. Some nights I test myself against bonfires and homemade apple pie shine, and wake up naked, erased. This is no surprise: the degree of damage a fire does to a tree depends on a number of factors—fire intensity, bark thickness. Corkscrew willow bark is thin and delicate.

In an undulating avalanche of college student bodies, we discover ourselves, whether we are flora or fauna, as we play our poison games. I may be a willow, but I wear my animal father’s skin and walk among the wolves when I want to. I poison myself in the dark, I dance with them while I am dying, I convince them I have fangs, too. I treat my leaves like dirty dollar bills and spend them easy, and Sunday mornings I scrounge for change to buy bottles of water when the thirst hits, when my body reminds me what I am, what it is owed.

***

Any number of things might kill the corkscrew willow—fungus girdling the trunk, drought, pests. Improper watering and disease can weaken the tree until it succumbs. And men, of course—injecting glyphosate into the stem and waiting for the tree to droop and die, spraying it on the foliage, or cutting down the tree, applying herbicide to the mourning stump, ignoring the burn, stealing its ability to stretch to the sky.

When I am twenty-three, states away working on a Ph.D. and nine hundred miles from home, my mother calls to say that my father traded beer for cocaine and shouting fits for his fists. I find my animal skin easily and slip it over the twists and turns of this body’s bark as I rang old numbers. I do not tell her wow my cotton-dry mouth willow-wrenches around those old names, tongue coiling around vowels, calling in favors covered in dust. How they remember me. How they promise to find his white Ram and rip it to the rims, how I know these are people who keep red promises. How I make them promise me anyway. How they ask if I prefer to have his body found, or not. Whether I want it found whole, or not.

A tree can lose a limb in a storm and live on unperturbed, an animal has a much more difficult time. The curly willow is known for kinked foliage that drops to expose bare and twisted twigs, a body more interesting nude, crooked secrets unmasked by the trials of winter.

I do not tell my mother I do not balk at murder, that what stays me is her tender heart, that she might grieve, how it kills me to let him live. How I have to live with the years her idiot God gives him. How, when the woman who time’s thorns have only made more holy calls to cry that his tires were slashed, everything he owned stolen and smashed, how even the blanket I made him was gone and he might freeze to death while high, I hum How sad, how awful, holding pictures as proof, twisting the aching branch of my neck to get out the kinks. It is December, after all, and we corkscrew willow women are more brittle in wind and ice.

Trees have memory. They record things biochemically, recording past stresses like drought in their growth rings and epigenetics, which can influence how they respond to similar conditions in the future. I pour cola into the spiced rum in my cup. Alcohol may not intoxicate plants, but it can inure them to drought. It helps close the stomata, reducing water loss through the leaves, and serves as an alternative fuel source when water is scarce. And it comes in handy to learn how to survive when parched, pulling up those old memories, pouring in soda until you have that perfect half-inch head of foam.