Jen Knox (JK): Hi, Cindy! Thanks for joining Unleash. You are an Unleash Press author and regular contributor now to our publications. We’re dying to know a little about your journey as a writer/artist.

Cindy Hochman (CH): At the risk of dating myself on the very first question, I would say that my literary journey actually began 60 years ago, at the ripe old age of 6 (and now you and everyone else can do the math!). As recounted in my flash fiction piece “Swan” (it’s in the chapbook so beautifully published by Unleash Press), my dad was an attorney and also a would-be poet. By day he wrote legal briefs (a misnomer if ever I’ve heard one, since legal briefs are anything but brief) and by night he wrote poetry, but not free verse the way we do today; he wrote the kind of rhyming poetry that is a bit out of fashion now. And he would give my brother and me what would now be called prompts and the three of us would have to come up with a poem. And, young as I was, I do remember putting pen to paper and always writing something. My dad was a fan of words and literature, so I think writing is in my genetic make-up.

At age 12, I wrote what I considered to be my first “serious” poem. I wish I had saved a copy of it, but of course I no longer have it. However, I do remember one phrase from it: “the iridescent glow of the now tear-stained mirror.” (I guess at the time I assumed that poets were supposed to write dark poems, so that was my aim.) But I discovered around the same time that I had a flair for writing parodies too, and they were lighter and more humorous. And here I owe a debt of gratitude to Ms. Susan Edelson (Spiro), my seventh-grade English teacher, who happens to be a friend of mine on Facebook, for giving assignments to write parodies. And I should note that Ms. Edelson gave me a B+ for one of those “masterpieces,” but recently, after much cajoling on my part, she relented and changed it to an A.

Now fast-forward to age 21, which is when I realized that writing poetry was to become my lifelong passion. I began actively seeking out poetry workshops and started submitting my poems to journals and, like every poet, got plenty of rejections but also a few acceptances (including a $5 check that, to this day, I have never cashed for some reason).

And the rest, as they say, is history ...

JK: It seems poetry has been a constant companion. That said, sometimes writers struggle to know what advice to take (and what to leave). What is the best piece of advice you've received as a poet?

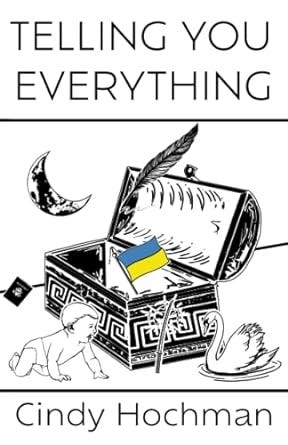

CH: Ah, do you mean the well-meaning but wholly insulting person who told me that maybe I should take up knitting instead? No, just joking. Actually, the advice that I’ve internalized the most is the much-cited edict to “write what you know.” I think that has given me permission to use the dreaded vertical pronoun that we’re cautioned not to use; that is, I write about myself because I know myself (heck, even the great Walt Whitman said “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” and if it was good enough for Uncle Walt ...). Of course, the so-called confessional poets, such as Plath and Sexton, had no qualms about writing “me-me-me” poems. And although I do try to observe the world and write about things outside of myself, I believe most writers throw a ton of their own selves, heavy baggage and all, into their writing. So I guess giving my chapbook the title Telling You Everything was no accident—though I didn’t set out to write an autobiography, reading the poems now makes me think I kind of did.

JK: Please share with us one (or a few) of your favorite lines, either from your own work or someone else's work, and explain what strikes you about the passage.

CH: Oh boy, I could probably fill several notebooks with a list of favorite lines. I’ll start with the much-quoted wheelbarrow poem by William Carlos Williams: so much depends upon a red wheelbarrow ... there’s something so profound about this brief poem of his, and of course it makes a great epigraph. That line also makes a good starting point for the aforementioned parody, and I’m sure I’ve written a bunch of silly “so much depends upon ...” poems.

As stated above, I have a taste for humor, and although his poems are often seen as trite doggerel, I never fail to chuckle at Ogden Nash’s pithy one-liners, such as If called by a panther / don’t anther and In the Vanities / no one wears panities (which immediately makes me think of adding a line about Sean Hannitys, though perhaps I should leave that one alone). I actually did use one of Nash’s absurdities for an equally absurd poem of mine; to wit:

Unemployment Insurance

I would live all my life in nonchalance and insouciance

Were it not for making a living, which is rather a nouciance.

—Ogden Nash

Unemployment insurance

is a test of endurance

the checks don’t come fastly

and the amount is quite ghastly

JK: How did you find your first publication?

CH: I remember it well. In my early twenties, that pivotal time when, as I said, I was first seeing myself as a “bona fide poet” (if there is such a thing), my brother gave me a wonderful gift: a copy of The Poets’ Market. Oh my, that reference book, which is updated every year, became my Bible. It contained a treasure trove of small-press journals (some of which are still around today), along with their guidelines, and I had a field day poring through them to decide where my work would be a good fit. Now, keep in mind that this was circa 1978, before computers, before online journals, so you had to type your poems the old-fashioned way (on a typewriter!) and snail-mail them to the editor, along with a self-addressed stamped envelope (known as a SASE) if you wanted to receive a response. To this day, I utilize the Poets’ Market, but of course now the process is much easier, since most publishers prefer submissions via email or Submittable. I was also lucky enough to meet an editor of an experimental poetry journal and he gave me a whole list of his publisher friends who might be interested in my work, and sure enough, I started getting published fairly regularly (no doubt “with a little help from my friends”). But now if a journal should send me a $5 check, I’d most likely cash it, go to the nearest café, use the dough for an inspirational latte, and hopefully go home with a new poem in my notebook.

JK: What are you working on next?

CH: I don’t quite remember how I got started with this, but I’ve been writing a series of alliterative poems. I believe I’ve written about 15 of them so far, each using a different letter of the alphabet and varying themes for each. They are all prose poems and I hope to come up with eleven more so that I can complete the alphabet and have ... perhaps ... a chapbook? They’re fun to write, and even more fun to read out loud (which I’ve been doing at various open mics on Zoom), and a number of them have been published individually (most notably, in SurVision Magazine and Poetry Pacific).

I also continue the collaborative project begun in 2017 with Bob Heman. Yes, we’re still at it, and as of this date, we’ve written 217 of them, four of which we’ve just submitted to Rattle Magazine, which happens to be doing a collaborative poetry issue. I have a long history of Rattle rejecting all my poems, and I even wrote a snarky little poem about that (which they, of course, also rejected), so it would be poetic justice if they accepted one of them. I’ll keep you posted!

Thanks, Jen, as always, for all the “airplay” you give to Unleash’s authors. I feel mighty proud to be on your roster and I wish you much success in all your future creative endeavors, both with Unleash and with your own awesome writing.

Thank YOU, Cindy. Your wisdom is generous, and we are honored to share your words.

Cindy Hochman is the president of “100 Proof” Copyediting Services and the editor-in-chief of the online poetry journal First Literary Review-East. She has been on the book review staff of Pedestal Magazine, and has written reviews for American Book Review, Clockwise Cat, Home Planet News, great weather for MEDIA, and others. Her previous chapbooks are Wednesday’s Child (Bear House Press), The Carcinogenic Bride (Thin Air Media), Habeas Corpus (Glass Lyre Press), and The Number 5 Is Always Suspect (Presa Press), a collaborative chapbook with poet/collagist Bob Heman. Cindy lives, loves, reads, writes, edits, meditates, learns tai chi, studies Russian, and agonizes over politics in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, and despite what she says in the poem “Poet Bio,” she has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her latest chapbook, Telling You Everything, was released in 2022 by Unleash Press.

Cindy, I'm delighted by your Nash quotes. His writing is a wonderful reminder that the best humor is deeply truthful. Hey, who says the literary life can't be fun?